A man once came to me struggling with the problem of suffering. He said he just couldn’t understand why God would allow something like a tsunami to wipe out so many people, including children. We had already met a few times about this topic and had been through all the points that we’ve covered for the past three weeks. Maybe he didn’t understand because because he was still living for level one and two happiness or because he had never experienced God’s love for him. I know for sure that, though Catholic, he didn’t really embrace the truth of eternal life. He said, “But all those kids never had a chance to grow up.” And I said, “Oh, you think their life wasn’t fulfilled because you think the point of life is to live to 70 or 80 years old—that’s not the point of life.” He then said, “I think you’re on to something.”

A man once came to me struggling with the problem of suffering. He said he just couldn’t understand why God would allow something like a tsunami to wipe out so many people, including children. We had already met a few times about this topic and had been through all the points that we’ve covered for the past three weeks. Maybe he didn’t understand because because he was still living for level one and two happiness or because he had never experienced God’s love for him. I know for sure that, though Catholic, he didn’t really embrace the truth of eternal life. He said, “But all those kids never had a chance to grow up.” And I said, “Oh, you think their life wasn’t fulfilled because you think the point of life is to live to 70 or 80 years old—that’s not the point of life.” He then said, “I think you’re on to something.”

He saw the goal of life as something earthly. I don’t blame him. That’s how we’re raised in this culture. But that’s not the truth. When children die, it is a tragedy. But, thank God, it’s not an eternal tragedy. God is already taking care of those children and drawing them to Himself. We talked two weeks ago how we have this incredible confidence that children who die before they can sin are in heaven.

But the question remains: why does God allow suffering?

We have to break the question down into two parts: 1) Why does God allow suffering caused by other humans? 2) Why does God allow suffering caused by the blind forces of nature (e.g. earthquakes, famine, disease, etc.)?

1) God allows us to hurt each other because that’s the condition of freedom. Freedom to love must include freedom not to love. If God forced us to love each other and never hurt each other, then we’d be robots. He doesn’t want us to hurt each other, but freedom, by definition, demands the possibility that we can say, “No.” If we’re not free to choose the bad, we’re not free to choose the good. (Note that God never created suffering, but He did create the possibility for suffering, which is necessitated by love.)

We have to be free to choose un-love, in order that our love might be our own. If we’re forced to love, then that’s not being made in the image and likeness of God, with the dignity of God Himself. The only way He can give us the ultimate dignity of being made in His image is to give us the possibility of choosing un-love.

Computers don’t have freedom, animals don’t have freedom. Babies actually don’t have freedom, not yet; it’s there but not yet actualized. They’re beautiful, precious and sacred, but they’re not yet virtuous, honest, and courageous—they need freedom to develop these characteristics. The time will come when their freedom develops, and they’ll be able to choose to be honest or dishonest, courageous or cowardly, hard-working or lazy. One of the most beautiful things in the world is to see our children grow up, leave the house, and without any pressure from us, freely choose to be self-controlled, faithful, polite, compassionate, etc.

Yes, people abuse it, we all abuse it, but it’s still one of the greatest gifts God has given us. The gift to freely choose love is better than being a robot.

2) Why does God allow suffering caused by nature? This is a harder question, but gives an even more beautiful answer.

Fr. Spitzer’s own father explained it this way. Did you know, if there were no fear because there were no possibility of pain, no possibility of embarrassment, and no possibility of death, then we’d never know if we had any courage? If there were never any possibility of failure, difficulty, or challenge, we’d never know if we had constancy, determination, that we’re capable of great sacrifice, and that we’re able to defend an ideal or defend a person? Everything has a cost. If we’re going to display self-sacrificial love, then we’re going to have to sacrifice something, which involves suffering. If God created a suffering-free world, we’d never know what we’re capable of. And we don’t have to do it for all eternity; we just have to do it for a short time so that we know who we are, we define ourselves.

Fr. Spitzer’s own father explained it this way. Did you know, if there were no fear because there were no possibility of pain, no possibility of embarrassment, and no possibility of death, then we’d never know if we had any courage? If there were never any possibility of failure, difficulty, or challenge, we’d never know if we had constancy, determination, that we’re capable of great sacrifice, and that we’re able to defend an ideal or defend a person? Everything has a cost. If we’re going to display self-sacrificial love, then we’re going to have to sacrifice something, which involves suffering. If God created a suffering-free world, we’d never know what we’re capable of. And we don’t have to do it for all eternity; we just have to do it for a short time so that we know who we are, we define ourselves.

When the Blessed Trinity created the whole world, they did it out of love. But we never knew how much they loved us, their self-sacrificial love for us; it was there but we couldn’t see it. So, Jesus, when He became man and entered a world where suffering was possible, showed that His love for us was unconditional by giving up everything. The saints, when they suffered, showed that their love is like God’s. When we suffer, it’s an opportunity to show what kind of love we’re capable of.

It’s either this world or living in a pleasure bubble. If God created us in a pleasure bubble, there’d be nothing for us to do: we couldn’t create or improve the world. We’d have no self-definition because we could never do anything for anybody, because God the hovering parent would go out and do it for us, and do it better than we. We’d never be able to sacrifice anything for anybody. The possibility of a perfect pleasure bubble is highly overrated because there’s no self-definition or growth.

God doesn’t want to hurt us, but, like any good parent, has to let us go. We cannot keep our children at home forever. Have we ever met people who loaf off their parents, never grow up, and have their parents do everything because for them? They never learn responsibility or take care of people. To allow this would be to limit our children to being infantile and enable bad habits. That’s not loving. The more loving thing to do is to guide, teach and discipline them, but the time comes when they have to make it their own.

And God will help us. But He needs some goodwill, desire, and effort. Just like any good coach or teacher, He can’t do it for us. We have to practice, and practice involves suffering; it’s never all fun. Perhaps God’s greatest gift to us is letting us choose who we’ll become.

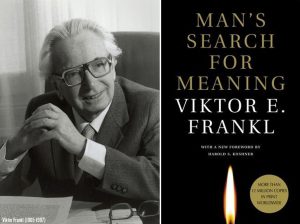

Victor Frankl wrote a famous book, Man’s Search for Meaning, about his experience in the Nazi concentration camp in Auschwitz during the holocaust. He went through forced labour, torture, and cruelty; his parents, brother and wife all died in the concentration camps. Being a psychologist, he sought to understand the meaning of suffering.

In the concentration camps, he noticed that some prisoners chose to help the Nazis to make life easier for them (they sold out), some chose to merely survive, while some men chose to rise above their sufferings.

He remembers, for example, the goodness of one man: “On returning from work, I was admitted to the cook house after a long wait and was assigned to the line filing up to a prisoner-cook F___. He stood behind one of the huge pans and ladled soup into the bowls which were held out to him by the prisoners, who hurriedly filed past. He was the only cook who did not look at the men whose bowls he was filling; the only cook who dealt out soup equally, regardless of recipient, and who did not make favorites of his personal friends or countrymen, picking out the potatoes for them, while the others got watery soup skimmed from the top” (Man’s Search for Freedom, 58). Imagine that! A person who, under terrible circumstances, is still fair to other people and treats all with equal love!

He also remembers “the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way” (75).

This is our greatest gift: our freedom to choose who we are, self-definition! Anyone can be patient when they’re healthy and things are easy. But then we see who is really patient when they’re sick, tired or under pressure.

Frankl says: “A human being is not one thing among others; things determine each other, but man is ultimately self-determining… In the concentration camps… we watched… some of our comrades behave like swine while others behaved like saints. Man has both potentialities within himself; which one is actualized depends on decisions.”

While animals can only be animals, humans can either act better (like God) or worse (like animals). Animals follow instinct: they eat, sleep and reproduce. When they eat other animals, they’re acting in accord with their nature; we don’t sue them for animalcide. Humans are different: when we’re hard-working, disciplined, kind and temperate, we’re acting like humans. When we’re lazy, gluttonous, mean, lustful, we’re acting like fallen humans. When we do horrible things, atrocities, we’re acting like animals, letting go of our reason and following our base desires. But when we sacrifice, exercise amazing discipline, do what is right when difficult, we’re acting like God. Alexander Pope wrote: “To err is human, to forgive, divine.” Making mistakes is part of being human, but to forgive is who God is.

There is, however, one thing on which I disagree with Frankl. He says, “Naturally only a few people were capable of reaching great spiritual heights” (80). That’s not true because God’s grace is available to all of us. But Frankl’s right when he says they’re the minority and we’re challenged to join the minority. We all have the “chance to attain human greatness” and nobility.

Whatever suffering we’re going through or will go through, we have an opportunity to rise above our sufferings and love more, become more human, or become even like God.

Those who love more on earth are capable of receiving more love now and in heaven. Everyone in heaven will be perfectly happy, but some more happy than others. It depends on our capacity to love. Some of us have the capacity to love the size of a cup. When we enter heaven, that cup will be filled completely to the brim with love. But some of us have the capacity of a pot, while others the capacity of a bath tap, and so on. Just as it takes bigger muscles to lift heavier weights, so it takes a bigger heart to love while suffering. And that bigger heart can be filled with more love in heaven. That’s why God wants us to grow in love, so that He can fill us with more love. Everything He does is out of love, so that we can be even more happy in eternity.

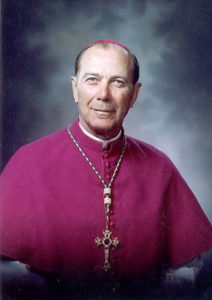

Archbishop Exner once described the length of eternity this way: imagine there’s a metal ball the size of the earth. Every 10,000 years, a large bird flies by this metal ball, brushing it ever so gently with its wing and scraping off a bit of metal. Every 10,000 years this happens and slowly, painfully slowly, the ball wears down. Imagine how long it would take to wear it down! After all that time, when the ball gets finally worn down to nothing, eternity hasn’t even begun yet! That’s how long it is! That’s how long our happiness is supposed to last. That’s why it’s so important to expand our capacity to love!

Archbishop Exner once described the length of eternity this way: imagine there’s a metal ball the size of the earth. Every 10,000 years, a large bird flies by this metal ball, brushing it ever so gently with its wing and scraping off a bit of metal. Every 10,000 years this happens and slowly, painfully slowly, the ball wears down. Imagine how long it would take to wear it down! After all that time, when the ball gets finally worn down to nothing, eternity hasn’t even begun yet! That’s how long it is! That’s how long our happiness is supposed to last. That’s why it’s so important to expand our capacity to love!

Frankl says, “Since Auschwitz we know what man is capable of.” When I first read this quote, I thought he meant: now we know how low man can sink. Then I realized it probably means this, but it also means we also know how high man can rise: that he’s capable of heroism, loving like God.

God allows suffering because the gift of freely choosing love is better than being a robot. God allows suffering because the gift of defining who we are is better than a pleasure bubble.