The first small step to a better marriage is to say, “I’m sorry.” So, how often do we say to our spouse, “I’m sorry,” or, “I was wrong, you were right?” (And it has to be done honestly and with sorrow, not, “I’m sorry you’re so sensitive,” “I’m sorry that you misunderstood me once again,” or “I’m sorry that you misrepresented my motivation.” (Scott Hahn, Marriage and Family, Track 6, 1:32).) Is that easy for us to do or hard?

The first small step to a better marriage is to say, “I’m sorry.” So, how often do we say to our spouse, “I’m sorry,” or, “I was wrong, you were right?” (And it has to be done honestly and with sorrow, not, “I’m sorry you’re so sensitive,” “I’m sorry that you misunderstood me once again,” or “I’m sorry that you misrepresented my motivation.” (Scott Hahn, Marriage and Family, Track 6, 1:32).) Is that easy for us to do or hard?

What about our spouse? Would they say, for example, “I’m sorry for taking you for granted,” “…for not telling you about that call,” “…for forgetting,” “I’m sorry I lied.” And do our children readily apologize to us or to their siblings?

We’re talking about pride, in the sense of falsely seeing ourselves as better than we really are and always trying to win arguments. If we suffer from pride, we’ll never reach our full potential because it’s hard for us to change, because change often means admitting that what we were doing before wasn’t best. We also have difficulties with other people because we always have to win discussions and so we don’t listen. Lastly, pride affects our relationship with God because we don’t trust Him.

What’s the opposite of pride? Humility. Jesus today gives us nine beatitudes, and the first one is, “Blessed are the poor in spirit.” What does being poor in spirit mean? Fr. Robert Spitzer S.J. says it means humility (Five Pillars of the Spiritual Life, 41-42). Humility is not about winning or losing or about appearing better than we are, but about truth.

Robert George is one of the leading intellectuals in the US right now, a professor at Princeton, and a devout Catholic; he’s brilliant and inspiring, but also humble. He tells a story about arguably his most important intellectual moment for him. He was in second year of college taking a course on introduction to political theory and had to read Plato’s dialogue Gorgias. One of the questions asked in it was: Why do we enter into discussion, debate, or argument? Is it to gain glory, enhance prestige, get ahead in life, rise up the ladder, uphold the honour of our group… or do we do it for sake of truth? If we do it for truth, then this changes how we do it and the attitude we take going in.

When George read the dialogue he was startled because he could see that he was on the wrong side of this question. He had always assumed that the point of discussion was to win (he was very good at debating and was a formal debater in high school), for the sake of one’s side like religion or a political party.

But Plato said that was a mistake; the real goal is truth! That means our interlocutor, if that person is honest, is our friend, not our enemy, and that, in a true discussion, even if we disagree, we’re bound by a common goal: getting at the truth. So, if we’re wrong on a point, then we want to lose the debate, it’s in our best interest to lose and get corrected. We shouldn’t be bitter; on the contrary we owe our interlocutor a debt of gratitude because he’s given us the greatest gift of all: He’s moved us from error to truth. This discovery changed George’s life and put him on the trajectory to becoming a university professor who loved truth, rather than a lawyer or going into politics because he had strong views and was good at debate.

(Start at 59:13)

What about us? Do we like getting corrected? Humble people do. They say things like, “Thank you for telling me,” “I didn’t know that,” or “I was mistaken. I’ll change my mind on that.”

One time, I had to give very negative feedback to someone. Another person asked, “Are you sure? I don’t think he’ll take it well.” “Yes, he will,” I said, “He’s a man of virtue.” And he did. This man is so humble that he recently told me about how good it was for him to be corrected on the way he was giving his presentations. While it partially hurt, he loved becoming a better speaker and giving better service.

This brings us to relationships. Humble people happily apologize when they’re wrong. But there are two reasons why we struggle to apologize: 1) We say, “I don’t have anything to apologize for. I didn’t do anything wrong.” The reality is, in most family arguments or problems, both sides have made mistakes, and each should take ownership for their part. Even if the other person doesn’t apologize, we still should because it’s about truth. Even if we were only five percent wrong (e.g., by raising our voice or swearing, even if they provoked us to getting mad, or even if we were acting out of hurt, we should still apologize (Dr. Ray Guarendi, Marriage: Small Steps, Big Rewards, 4).

Anyone remember the catchy song A Little Bit Me, a Little Bit You by The Monkees? In it, they say, “I’m a little bit wrong, and you’re a little bit right.” That’s very true. Most of the time, it’s not about, “I’m all right and you’re all wrong.”

2) The second reason we struggle to apologize is because we think, “My apology will just convince them that they’re right and I’m wrong.” Not necessarily. If they exploit our apology and say, “See, you admit it: it’s your fault!” then we very calmly offer another true statement, “I admit I was wrong on that point, but I’m not all wrong.” (And that’ll really make them mad!) But, what’s more likely to happen is they’ll apologize for their share. By us showing vulnerability, they’ll let down their defenses too.

Lastly, in our relationship with God, humility is the foundation. During Jesus’ time on earth, He constantly taught His disciples to trust Him. So much of what He taught seemed hard and the disciples struggled with it. When Jesus taught about the Eucharist, for instance, most of the disciples left, but the apostles stayed behind. St. Peter asked, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life” (Jn 6:68). In other words, even if he didn’t completely understand the teaching, he still trusted Jesus. He knew that everything Jesus taught wasn’t meant to hurt us, just as many of us know the official teachings of the Church aren’t meant to hurt us. They can often be very challenging but are meant for our good.

Lastly, in our relationship with God, humility is the foundation. During Jesus’ time on earth, He constantly taught His disciples to trust Him. So much of what He taught seemed hard and the disciples struggled with it. When Jesus taught about the Eucharist, for instance, most of the disciples left, but the apostles stayed behind. St. Peter asked, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life” (Jn 6:68). In other words, even if he didn’t completely understand the teaching, he still trusted Jesus. He knew that everything Jesus taught wasn’t meant to hurt us, just as many of us know the official teachings of the Church aren’t meant to hurt us. They can often be very challenging but are meant for our good.

And there are good reasons for these teachings. Last week, when we offered some reasons for why only men can be priests, I would hope that people at least acknowledge that they’re not bad reasons and we don’t do things without thinking; there is some deep thought here.

But once again it’s a matter of trust. We could either say: 1) “The Church is wrong. The Church needs to get with the times. The Church doesn’t understand” people (Matthew Kelly, The Four Signs of a Dynamic Catholic, 21). This approach however seems not to want to understand the teachings or the reasons. Be aware that there’s a part in all of us that sometimes just doesn’t want to accept what someone says to us. Have we ever noticed that? It’s a kind of willful resistance or stubbornness. 2) The other thing we could say is: “I don’t understand this teaching. I should try and find out why. There must be a good reason for this. I trust Jesus, the Church He founded, and 2,000 years of the best Catholic minds.”

After last week’s homily, a woman told me that, when she became Catholic at age 13, she didn’t understand why only men could be priests. She knew from studying Scripture that Jesus deliberately chose only men even though He could have chosen women. But not knowing the deeper reasons, she decided to “press the pause button and just accept the tradition as something I shouldn’t mess with.” Years later she met some wonderful Catholics and teachers who showed her a new perspective on Catholicism. Through this and some reading, one day something clicked: She understood how Christ was the Bridegroom and the Church was the Bride, thus it was fitting that a man stand in the place of Christ.

Growing in humility starts with prayer. We humble ourselves before God the Father and say, “I need help. I’ve got a lot of pride. You’re all good and all loving, please help me to focus on truth, not on winning.”

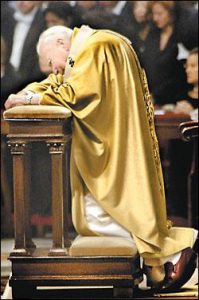

And, if I may respectfully share: I once knew a priest who could be very mean to people. It only occurred to me afterwards that, in the long time I knew him, I never saw him kneel in prayer; his attitude and approach was always one of commanding.

Contrast this with the father of St. John Paul II, who wrote, “By profession he was a soldier and, after my mother’s death, his life became one of constant prayer. Sometimes I would wake up during the night and find my father on his knees, just as I would always see him kneeling in the parish church” (Pope John Paul II, Gift and Mystery, 20).

Contrast this with the father of St. John Paul II, who wrote, “By profession he was a soldier and, after my mother’s death, his life became one of constant prayer. Sometimes I would wake up during the night and find my father on his knees, just as I would always see him kneeling in the parish church” (Pope John Paul II, Gift and Mystery, 20).

Before my father’s conversion, he never knelt, because I think he had a lot of pride. After his conversion, it was so amazing to see Dad make the Sign of the Cross, join his hands in prayer, pray the Rosary (which is a simple and humble prayer), and go to Confession, because he was more humble and more secure in himself.

Humility is very liberating! We no longer have to make ourselves look perfect, try to win or prove ourselves right. It also makes for better relationships. Humility is about truth.