There’s a famous story about Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple. When he was 13, he saw a photo of starving children in Nigeria. Disturbed by this, he went to his Lutheran pastor and asked, “If I raise my finger, will God know which one I’m going to raise even before I do it?” “Yes, God knows everything.”

Then Jobs pulled out the photo and asked, “Well, does God know about this and what’s going to happen to these children?” “Steve, I know you don’t understand, but yes, God knows about that.” After that incident, “Jobs announced that he didn’t want to have anything to do with worshiping such a God, and he never went back to church” (Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs, 14-15). Many of us and our children ask a similar question to Jobs’.

Nevertheless, before we explore the answer, let’s say right away that Jobs’ conclusion isn’t the only one out there.  Pastor Andy Stanley once took his three children, ages ten, twelve, and fourteen, to a slum in Kenya where half a million people live in three square miles; there’s no running water or electricity, and people throw their excrement into the same river from which they drink. When they saw this, his three kids and the other kids on this trip didn’t lose faith; they were actually motivated to do something about the situation (Andy Stanley, Deep & Wide, chapter 8).

Pastor Andy Stanley once took his three children, ages ten, twelve, and fourteen, to a slum in Kenya where half a million people live in three square miles; there’s no running water or electricity, and people throw their excrement into the same river from which they drink. When they saw this, his three kids and the other kids on this trip didn’t lose faith; they were actually motivated to do something about the situation (Andy Stanley, Deep & Wide, chapter 8).

The question today is: What is God’s will regarding suffering? For what does He hope? What’s supposed to come out of suffering? The First Reading from the prophet Isaiah, written in the 6th century B.C., starts with this shocking sentence, “It was the will of the Lord to crush him with pain” (Is 53:10). There are three things we can say about this: 1) About whom is Isaiah speaking here? Jesus. So, “it was the will of the Lord to crush [Jesus] with pain.” Now we need to remember that Jesus is God, so it was His own will to crush Himself with pain.

2) In theology, we distinguish between two wills of God: His indicative (or perceptive) or positive/ideal will and his permissive will. His indicative will is what He wants; His permissive will is what He allows. He indicates, for example, that He wants us to love Him; but He permits us to sin, and allows things like starvation. God didn’t want and didn’t cause the crucifixion—it was the result of misused human freedom—but He allowed it. So, when the reading says “it was the will of the Lord to crush him with pain,” it means that God allowed it, and then used it for a greater good.

3) The reading is actually focused on this greater good; it indicates seven graces that will come out of Jesus’ suffering: “When you make his life an offering for sin, (1) he shall see his offspring, and (2) shall prolong his days; through him (3) the will of the Lord shall prosper. Out of his anguish (4) he shall see light; (5) he shall find satisfaction through his knowledge. The righteous one, my servant, (6) shall make many righteous, and (7) he shall bear their iniquities” (Is 53:10-11). So, this reading actually focuses on the blessings that come from the suffering of the servant of God.

This is our answer to the question: What is God’s will regarding suffering? He wants to bring about a greater good.

Now, whenever we see someone suffering, whether it’s with a headache or something more serious, we don’t start with, “Did you know that God’s permissive will allows this for a greater good?” No. We start with, “Can I do anything for you?” We suffer with them. But, after that, because the human person always desires to understand their suffering, we can offer them a different way of looking at suffering. Remember, there are three conditions to understanding suffering:

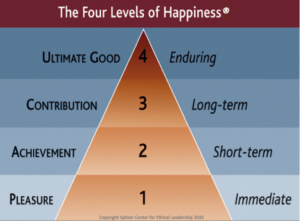

1) Do we believe there are different levels of happiness? According to Fr. Robert Spitzer, S.J., 70% of us live at either level one or level two, which is immediate gratification and ego satisfaction. Our focus is on having fun, working for the weekend, getting not what we need, but what we want; we love buying stuff and achieving—there’s nothing wrong with that in and of itself, but, if we live at these levels, we become selfish, entitled, and narcissistic; and we will neglect God, family, and friends.

2) God, like any good father, when He sees His children becoming less than saints, will lead them to higher levels of happiness by teaching them; but if that doesn’t work, He’ll take away levels one and two happiness and that will cause suffering—that’s tough love, but it is love. This is the second condition: Do we believe God always loves us, and therefore allows suffering for our good?

3) The third condition is eternal life. If this is our only life and most of it is spent in pain and not achieving a happy life, then suffering makes no sense. However, if our life on earth is just a tiny fraction of our whole existence and we’re preparing ourselves for heaven, then it makes sense that suffering can prepare us for the next life.

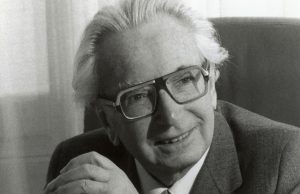

And this leads us to two things which God hopes to see from suffering. First, self-definition. Suffering allows us to define who we are. Remember the example of Viktor Frankl in the concentration camps? He was a Jewish psychologist, and wrote that some men acted as men, just trying to survive. Yet, others acted as beasts, selling out their own people and cooperating with the Nazis in order to save themselves. But some rose above their suffering and acted as angels: They went through the huts comforting others, giving their last piece of bread to someone else.

At the seminary in Mission, the high school seminarians play sports every day, while the college seminarians have mandatory sports twice a week. Why? Someone famous said, “Sports don’t build character, they reveal it.” Let’s see who’s really patient, hardworking, a team player, who has endurance, fortitude, humility. While I loved mandatory sports, Fr. Anthony Ho hated it; but he always participated out of obedience. (He also came late and left early but that’s another story.)

Now some people object: If God were a good father, He wouldn’t allow His children to suffer. Not so. There’s a famous TED talk on vulnerability, where psychologist Brené Brown says “children are hardwired for struggle when they get here” (17:58). Consequently, if we try to give them a perfect life where there’s no pain, failure, or difficulty, we actually hurt them.

I did a funeral here once. Before her death, the woman told her sister that her children were all selfish. The deceased originally came from another country and had to work hard to build a better life, but her children got everything easily and they never visited her.

It’s a world where there is either suffering or the pleasure bubble, where God protects us from any difficulty. But then we never get to grow in love because we can never sacrifice. And what do we get when there’s no struggle in life? As Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn says, people who don’t struggle are spiritually and morally weak.

I had an epiphany recently. I read from an experienced pastor how good it is for a parish to struggle to raise money because that’s when we learn to trust in God and we get to sacrifice our own money (Bill Hybels, Courageous Leadership, 101-102, 104)! Have you heard that some people have fantasized about winning the lottery? Wouldn’t that be great? Then we’d get our parish centre easily? No way! Because if someone did, then we’d lose the opportunity to give our own money in sacrifice! I now understand. It was a gift from God that I was able to give half of my savings to the fundraising, because now I’m closer to loving as God. God wants this parish centre, and if we want it as much as He does, we’ll give as much as He does, that is, everything, a sacrifice.

The question this week for us is: When we suffer, what will be our response? We get to define ourselves.

The second thing God wants from suffering is an increase of love in the world. Archbishop Sheen once talked about a group of Christians in Russia called the Urodivoi (See video at 19:40). When they were in concentration camps and someone was about to be beaten, the Urodivoi would ask to be beaten instead of the other. Their argument was: If a regular prisoner were beaten, he would hate back; therefore, there would be an increase of hate in the world. If, however, the Urodivoi were beaten, they would forgive, and there would be an increase of charity in the world.

You see, whenever there’s a natural disaster, God allows it because He hopes that there will be an increase of courage in the world. When one of us gets cancer, He hopes there will be an increase of human solidarity: more love, care, and compassion.

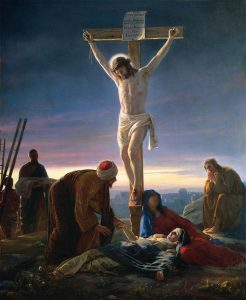

When Jesus died on the cross, He took on all the evil in the world, all that there ever has been, and all that there ever will be, so there was the greatest concentration of evil on one person. And as the evil upon Him increased, He kept on giving more love, and perfect love was given, and perfect love was shown. This is why the Mass is the centre of our parish, because it’s a renewal of Jesus’ self-offering and love on the cross.

When Jesus died on the cross, He took on all the evil in the world, all that there ever has been, and all that there ever will be, so there was the greatest concentration of evil on one person. And as the evil upon Him increased, He kept on giving more love, and perfect love was given, and perfect love was shown. This is why the Mass is the centre of our parish, because it’s a renewal of Jesus’ self-offering and love on the cross.

God doesn’t want suffering, but allows it for our good: We get to define ourselves and we can increase love in the world.