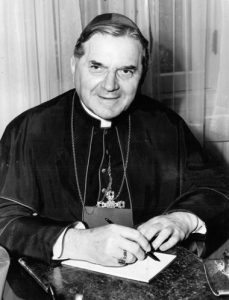

Here are two fascinating stories (and let’s pay attention to our conscience when we listen to them). Archbishop Joseph Rummel was the bishop of New Orleans during the 1950s, when there was still much racism in his area. Even though the bishops always made sure that black Catholics could get an education, his diocese still had separate schools for white and black children, but the schools for black children always had less money and were of worse quality.

Around this time, Archbishop Rummel started desegregating his church: The seminary started welcoming black men in 1948; three years later, the churches took down the signs that indicated if a church was for whites or blacks. Two years after that, he wrote a pastoral letter that was to be read during all Sunday Masses. He said, “There will be no further discrimination… in the pews, at the Communion rail, at the confessional and in parish meetings, just as there will be no segregation in the kingdom of heaven.” However, some Catholics resented hearing priests talk about this from the pulpit.

In 1956, he announced that he would aim to desegregate Catholic schools. “Tempers ran hot. Most parish school boards voted against desegregation. [But he] didn’t budge. A year earlier, he had closed a parish when its people objected to their newly assigned black priest” (Archbishop Charles Chaput, Render Unto Caesar, 56). Five years later, when he said he would integrate white and black students in Catholic schools, “several Catholic politicians organized public protests and letter-writing campaigns,” so Rummel excommunicated three of their leaders.

How do we feel about Archbishop Rummel? How do we feel about those Catholics who were racist? In the end, the New York Times praised his courage because he followed religious principle and the social conscience of the time.

Skip ahead to 2004. Archbishop Raymond Burke, bishop of La Crosse, Wisconsin, “asked three Catholic public figures to refrain from presenting themselves for Communion. He then asked his priests to withhold Communion from Catholic public officials who supported” so-called abortion rights. The three public figures said they were only pro-choice, but in fact they supported “forcing Catholic hospitals to provide abortions.” Thus, since they were actually supporting the killing of children in the womb, were publicly disregarding their faith, and were forcing their own Church to take part in killing, Burke wouldn’t allow them to receive Communion, which is a public statement that one believes in the Church’s teachings and is united with the Church.

Now, many people, even Catholics, objected to Burke’s stance. And he got no praise from the New York Times for following religious principle and doing the right thing. Hmm.

Let’s ask three questions based on these two stories: 1) Should Catholics take public stands on morality? 2) Should Catholics fight for their beliefs? 3) Is it right to force one’s beliefs on other people?

The starting point for our answers is what St. Paul teaches in the second reading, “An obligation is laid on me, and woe to me if I do not proclaim the Gospel!” (1 Cor 9:16). But it’s not only an obligation; it’s also a desire! He wants to win and save all people and he’s willing to adapt himself to whatever people need.

Here’s why. When we know a truth and love people, it’s natural to share it. Now, we’re not talking about preferences (for example, telling all our friends about delicious Japanese Ramen food); we’re talking about something true and necessary. If I discovered the cure for breast cancer, wouldn’t it be loving to share it with people? And, if I didn’t share it, wouldn’t that be wrong?

St. John Paul II had a great insight: When we tell people about the Gospel of Jesus, that includes telling people about the value of each person (Evangelium Vitae, 2). To proclaim the Gospel means preaching against racism and abortion. The reason is: If humans are called to eternal life and to share the life of God, then human life is sacred, and it’s sacred even now. Whenever atheistic regimes took over a society and denied that there’s eternal life, how did they treat people? At least one hundred million murders (Dinesh D’Souza, What’s So Great about Christianity, 218-219). Why? Because whether they died later or now made no difference. However, whenever there is growth in Christianity, which believes in eternal life, what springs up? Hospitals, clinics, shelters, orphanages, etc.

Consequently, when we preach the Gospel of Jesus, it means preaching the dignity of each person. Here’s a beautiful quote: “The Gospel of God’s love for man, the Gospel of the dignity of the person and the Gospel of life are a single and indivisible Gospel” (EV, 2).

Now let’s answer our questions. 1) Should Catholics take public stands on morality? Definitely. Archbishop Rummel did the right thing: even though he was opposed by thousands of Catholics and non-Catholics, he had to stand up against racism in churches and schools. When people publicly stand up against bullying and sexual assault, they’re doing the right thing. And so, when Archbishop Burke forbade those three Catholic public figures from receiving Communion, he did the right thing, even though it’s politically incorrect.

Nevertheless people often say, “What about separation of church and state?” However, does that mean Rummel should not have said anything? Of course not. Why? Because ending racism isn’t a religious idea; it’s a human rights idea. Same thing with abortion—it’s not a religious belief; it’s a human rights belief. That’s why there are groups like Secular Prolife, which is for atheists, agnostics, secularists and humanists who are against abortion.

Does separation of church and state mean only atheists can speak out? We’re citizens like everyone else and we have a right to be heard. The truth is: People say the pro-life movement is religious just to marginalize it. When public officials say, “We don’t tell church leaders what to do, why should church leaders tell us what to do?” We can respond, “Sure you do! You’ve told us to get our act together on the clergy abuse crisis. And you were right, because you have a duty to protect children. And we will tell you to stop abortion because we have a right to protect children” (Fr. Frank Pavone, Ending Abortion, 166).

2) I think the answer to our next question is obvious: “Should Catholics fight for their beliefs?” This human rights issue is essential and grave right now (100,000 babies are killed in the womb every year in Canada). This doesn’t mean doing evil, but it will involve making people uncomfortable. Ending racism made people angry. Even Catholics will oppose doing the right thing. But Jesus says, “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake” (Mt 5:10).

3) Is it right to force one’s beliefs on other people? No, because belief must be free. However the law can force people to act a certain way. The law forces us not to kill each other. It doesn’t tell us what to believe, but what to do. Why? Because it’s the right thing to do. In the same way, the law should stop people from killing babies, and we should campaign to get our law to do this.

The first step is to pray. Let’s pray for an end to abortion, let’s pray for our country to uphold human rights.

The first step is to pray. Let’s pray for an end to abortion, let’s pray for our country to uphold human rights.

But the second step is also necessary: We have to do something about it. Perhaps not everyone’s ready for it, but I pray we eventually will be: 40 Days for Life is for us on the Friday and Saturday after Ash Wednesday, which this year falls on Feb. 14. 40 Days for Life is an opportunity to pray and take a public stand. It’s just one or two hours for each of us. But it bears fruit.

I often think of the horrors of racism: the meanness, the beatings, the lynchings, treating black people as animals. And then I think of people like Archbishop Rummel, who was filled with the Holy Spirit and fought for the downtrodden. His example inspires me to be a better Christian and a better priest. And he, of course, was following Jesus.

We heard in the Gospel today that, very early in the morning, while it was still dark, Jesus went out to a deserted place and prayed. Everyone started to search for Him and when they found Him, said, “Everyone is searching for you” (Mk 1:37). And He said, “Let us go on to the neighbouring towns, so that” He may do something. And that something, He says, is what He came to do. Please open your missalettes to page 189. I’ll let you read the answer yourselves (Mk 1:38). He came to do this something, and we came to do it too.

[Answer: “Let us go on to the neighbouring towns, so that I may proclaim the message there also; for that is what I came out to do” (Mk 1:38).]