In June of this year, I read an article by Sohrab Ahmari, an Iranian who converted to Catholicism in 2016, and about his anxiety as a new father. The anxiety wasn’t about his son’s health, education, or anything like that, but, “What kind of a man will contemporary Western culture chisel out of my son?”

He worried that his son would grow up comfortable but without moral purpose. He wrote, “What if my Max at age 47 is touring Europe with his girlfriend in a luxury electric RV, the two of them having cohabited on and off for nearly a decade now, with no intention to marry, much less have children?… This is the… optimistic scenario… It assumes he hasn’t become one of those young men who spend… years shut in their bedrooms, playing videogames and browsing the web.”

The question, ‘What kind of man will my son become?’ revolves around the nature of freedom. Ahmari lived most of his life prior to becoming Catholic, with the modern sense of freedom: partying on the weekend, choosing your identity (which is fluid): high school misfit, college socialist, neocon lawyer. He could get a girlfriend, cheat on her, then dump her. Because freedom here means the ability to do what we want.

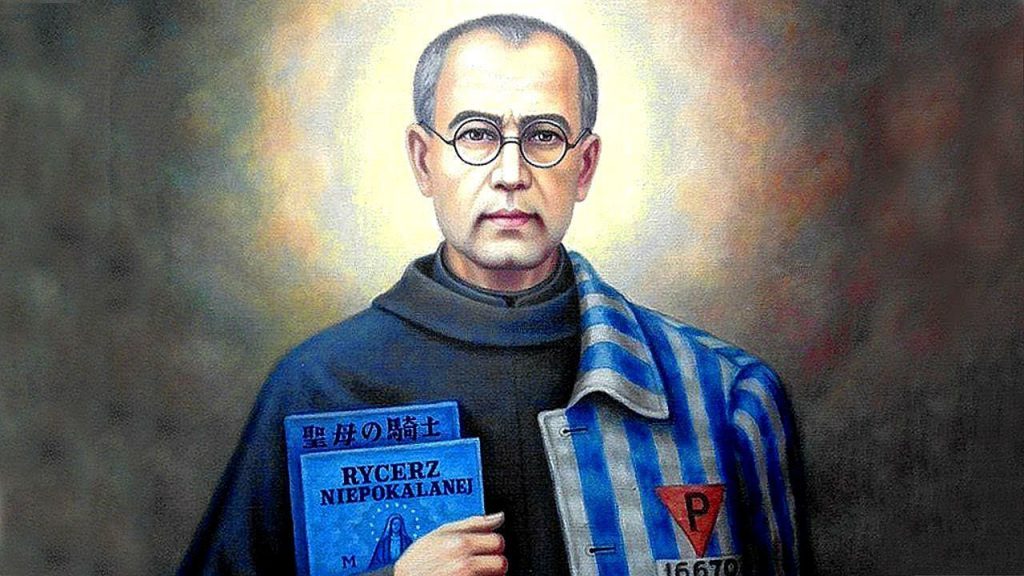

But he read a story that showed a different kind of freedom, a story about St. Maximilian Kolbe. Born in Poland in 1894, St. Maximilian Kolbe joined the Franciscans at 16, studied in Rome, came back to Poland, “where he started a newspaper, a radio station and a monastic community… Then came the German invasion of Poland… In 1941, the Nazis arrested and sent him to Auschwitz.

One night in July, an inmate escaped from Kolbe’s block. The camp’s deputy commandant, Karl Fritzsch, carried out his protocol for when inmates escaped: randomly selecting ten men to die of starvation as collective punishment for the one escapee. Kolbe wasn’t among those chosen to die. But when he heard one of the condemned cry out, ‘My wife! My children!’, the priest stepped forward. ‘What does this Polish pig want?’ Fritzsch asked. Kolbe replied, ‘I would like to take his place, because he has a wife and children.’ And so he did, laying down his life for a complete stranger.”

Ahmari said he couldn’t get this story out of his head. What if we were standing in that line-up: We couldn’t have done what St. Maximilian did. His freedom to volunteer to die is what gripped Ahmari. He called it a “perfect form of freedom.”

Jesus’ words today are about freedom: “Whoever wants to become my follower, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, and whoever loses their life for my sake, and for the sake of the Gospel, will save it” (Mk 8:34-35). To be a follower of Jesus means to deny ourselves good things so as to achieve the best. Remember what one monk said explaining why he chose to follow Christ: “I gave up a good life for a better one.” Some of you might remember the image of the five doors. Imagine we’re in a chamber, and before us are five doors, each representing going to university, getting a job, hanging out with friends, sports, and travelling. Most people want to do all of them simultaneously—is that freedom? Because if we try to do all of them, then we can’t commit to doing any of them well. True freedom, however, means closing the less important doors, and opening the most important ones. It means choosing the best door, because there’s another chamber behind that one with another five doors, which are better options! The point of freedom is to choose what leads to Christ.

Think of freedom with respect to our attitude. When someone disagrees or argues with us about COVID, do we have the freedom to remain calm and search for the truth? When we’re tired, do we have the freedom to stay committed to exercise? The next time you’re at Costco, notice people’s freedom or lack of freedom: Some are free to be courteous, some are not. When you go to a restaurant, some families are free to talk to each other, while others aren’t free; they’re absorbed in their phones.

In St. Maximilian’s case, he had two doors before him: Live or die in place of a stranger. Most people aren’t free to choose the second door. This sacrifice is what Jesus was referring to: When we’re able to lay down our lives for others, then we save our lives, meaning, we become like Him. That is the meaning of life, to become like Christ, because Christ is God, and He made us to become like Him. That’s what Ahmari is hoping for his son. That’s why he named his son Maximilian, so that there would be this thread between him and the saint, and his son would grow up free to choose what’s best.

In 2003, when Ahmari was in second year at Utah State University, he left a pornographic book on his Mormon roommates’ living room table, to shock their puritanical repression of freedom. However, one day, he picked up and read St. Matthew’s Gospel, which one of them had left on the couch. He said, “My frame of mind was contemptuous. ‘Here we go with the hocus-pocus, blah-blah, Jesus is born, blah-blah, Jesus tells a parable, blah-blah, Jesus performs a miracle, blah-blah, another parable” (From Fire, by Water, 106-107). But when he read chapter 26, about Jesus’ Passion, he was transfixed: Evil men betrayed and killed an innocent man, even though they knew He was innocent. More astounding, Jesus was strong and was able to stop them, but allowed these weak people to prevail. Ahmari writes, “What made Christ’s total surrender, when he could have vanquished his enemies in an instance (Mt. 27:51), so touching, even to an unbeliever? What was it about sacrifice… that left such a searing imprint on my mind? Why did I long for sacrifice?” (109).

Every human person deep down longs for sacrifice because this is where our freedom is perfected. Think about it: The greatest stories in our culture are about sacrifice: Jesus’ sacrifice, the sacrifice of soldiers, of single mothers. In fact, when you ask someone whom they admire, and ask for a story about that person, that story will revolve around difficult circumstances, when it would be difficult to choose what’s right, and that’s what the person did!

The goal of freedom is to become like Jesus. And Jesus is completely free, the Person Who always does what is good and loving, even when the greatest evil overwhelms Him.

It took Ahmari some years to reconsider his atheism, and then some more to become Catholic, but it began with the question that Jesus asks in the Gospel, “Who do people say that I am?” (Mk 8:).

This is our final week to invite someone to Alpha next week, as there’s a session that starts daily between Sept. 22-25, 2021. One of the greatest parts of Alpha is on the second night when they present ‘Who is Jesus?’ I wish I could show the beauty of Who Jesus is as well as Alpha does. In 25 minutes, they capture His uniqueness, and how the human heart finds answers and meaning in Him.

Ahmari wrote that his son may one day live a selfish, meaningless life but still say, “Dad, I’m happy!” and mean it. But he won’t know what he’s missing: “The thrill of meditating on the Psalms and wondering if they were written just for him; the peace of mind that comes with regularly going to Confession and leaving the accumulated baggage of his guilt behind; the joy of binding himself to one other soul, and only that one, in marriage; that awesome instant when the nurses hand him a newborn baby, his own.”

What kind of men and women will our children become? Today, see if you can discuss with them what freedom means. We hope they will be like Christ, because true freedom begins and ends with Him.

Lisa Rumpel says:

Thank you for sharing Ahmari’s story of conversion and concern for the health of his son’s soul. It is inspiring!