Dennis Prager, author and talk show host, asks an important philosophical question: “Do you believe people are born good?” He argues that we’re not born good. Babies, for example, are selfish: “I want mommy, I want milk, I want to be comforted. And if you don’t give me these things immediately, I’ll ruin your life.” Children can also be very cruel: They laugh at each other, bully the weaker person, or exclude unpopular children. Go to any school and we’ll find children doing things their parents never taught them to do, because sometimes children just naturally do bad things. We also have to teach them to say “thank you” hundreds of times. But, if they were naturally good, wouldn’t gratitude come naturally? Add to this, there’s so much evil in the world. There have been mass murders of hundreds of millions of people in the past century. And if people are basically good, why does every civilization have so many laws to guide human behaviour?

Dennis Prager

What do you think: Are people born good or bad? Parents, do you think your children were born good or bad? (You don’t have to answer that.) The answer has huge implications for how we live as individuals, how we raise our children, and how we behave as a society.

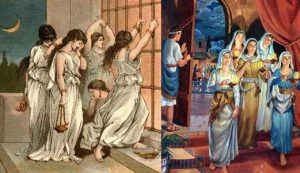

The reading from the Book of Wisdom and the parable about the ten bridesmaids point towards an answer. The Book of Wisdom says, “Wisdom… is easily discerned by those who love her, and is found by those who seek her. She hastens to make herself known to those who desire her” (Wis 6:12-13). In other words, no one is born wise; children are not wise. People only gain wisdom by looking for her.

In the parable about the ten bridesmaids, five are wise and five are foolish. They’re waiting for the bridegroom (Jesus) to come, but only the five wise bridesmaids take oil with them. And when Jesus arrives, the foolish ones aren’t ready. What’s the meaning? St. Hilary says that the waiting for the bridegroom signifies our lifespan, while the lamp signifies faith, and the oil signifies good works (Ignatius Catholic Study Bible, 53). We have no idea how long life will last, and, while many people have faith, they don’t have good works. And here’s the thing: No one is born with good works. They must be freely chosen during life.

In the parable about the ten bridesmaids, five are wise and five are foolish. They’re waiting for the bridegroom (Jesus) to come, but only the five wise bridesmaids take oil with them. And when Jesus arrives, the foolish ones aren’t ready. What’s the meaning? St. Hilary says that the waiting for the bridegroom signifies our lifespan, while the lamp signifies faith, and the oil signifies good works (Ignatius Catholic Study Bible, 53). We have no idea how long life will last, and, while many people have faith, they don’t have good works. And here’s the thing: No one is born with good works. They must be freely chosen during life.

So let’s go back to Dennis Prager’s argument. As Catholics, we believe all people are born good, because Genesis says we’re made “in the image and likeness of God” (Gen 1:26-27) and have incredible value and dignity (CCC 356). But, we believe no one is born virtuous, and I think this is what Dennis Prager means when he says ‘good.’

In homilies, we’ve used the term ‘virtue’ a lot, but never really explained what it means. A virtue is a quality of person who does something good repeatedly, so much so that it becomes a part of that person’s character (Cf. CCC 1804). So, for example, a person who repeatedly tells the truth, over and over again, builds up the virtue of honesty, and becomes an honest person. But a person who repeatedly lies actually builds up the opposite quality, the vice of lying, and, if done repeatedly, to varying degrees, that person will become a liar; lying will be part of who he or she is.

Let’s apply this to a concrete situation. We’ve baptized many babies recently. They’re beautiful babies, good, holy, cute, adorable, and so precious that Jesus died for them. Agreed? But they’re not morally virtuous, at least not yet. This isn’t something bad. Actually they’re fulfilling God’s will as they are. But the time will come when they’ll grow in knowledge and freedom and start making choices, and we pray that, by God’s grace and with our guidance, they’ll build up virtues.

Let’s apply this to a concrete situation. We’ve baptized many babies recently. They’re beautiful babies, good, holy, cute, adorable, and so precious that Jesus died for them. Agreed? But they’re not morally virtuous, at least not yet. This isn’t something bad. Actually they’re fulfilling God’s will as they are. But the time will come when they’ll grow in knowledge and freedom and start making choices, and we pray that, by God’s grace and with our guidance, they’ll build up virtues.

This has huge implications for all of us. It’s almost impossible to be virtuous if we don’t aim for it. Our culture, the media, and schools don’t talk about it, but tell us we’re already ‘good.’ So, if we’re already good, why strive for virtue? Jesus, on the other hand, tells us that wisdom and living well are only found by those who seek it; He expects us to be ready for Him with good works.

Are we virtuous? Generally speaking, there’s a simple way to figure out what’s a virtue. Ask, for example: Is it better to be honest or dishonest? Honest. So, how honest are we? Is it better, in general, to be on time or late? So, do we have the virtue of being punctual? What’s the better way to live: With self-control or without?

When Felix, our seminarian for the summer, left our parish, I told you that he’s an extremely virtuous person. The first time he came here, we were having a dinner downstairs, and he introduced himself to other people, because he has the virtue of friendliness and hospitality; when he talked to people, he was attentive and polite. When people started moving tables, he joined in without being asked, because he has the virtue of generosity and considerateness. (He didn’t even belong to the parish, but he pitched in!) I never had to remind him to go to the chapel to pray because he’s a prayerful man.

Virtue is one of the most beautiful things in the world because it’s a reflection of Jesus. Everything He did was virtuous: He always chose love and always chose the good, no matter how difficult. Deep down, we all have a desire to be like Him. St. Gregory of Nyssa says, “The goal of a virtuous life is to become like God” (CCC 1803). Once we get a taste of it, it’s addictive, in the best sense of the word: We want more of it; we want to do better and love more.

Have you heard this expression: Who you are is God’s gift to you; what you do is your gift to God. It points to something true: God loves us unconditionally and died for us. But we realize: We can’t stay as children. He gave us the ability to choose to become like Him, and by freely choosing to do the good, we praise Him.

This applies to our parenting. Prager points out that people who believe their children are born virtuous don’t spend a lot of time working on their children’s character—why should they? They’re already good. The focus, rather, is on blaming external forces (teachers, society, government) for why their children aren’t succeeding; it’s always someone else’s fault.

But parents who believe children need to grow in virtue spend a huge amount of effort, time, and money on teaching their children what is right and wrong, developing their character, disciplining them with love, showing them the narrow path that leads to heaven.

A mother (not at this parish) once told me that when her son, who has Down’s Syndrome, went to a new school in Grade 8, she was very worried about him because we all know that most kids unfortunately don’t want to hang out with someone who’s different. Most high school kids are not that virtuous when it comes to welcoming someone who’s different. But, on the first day of school, one of the other kids, who happened to go to the same parish, said to the child with Down’s Syndrome, “Hey, come sit with us!” When I heard this, I could have cried. That’s the kind of man we want to raise, who will do what’s right even when it’s not cool or not popular, who has the strength of character to include someone who’s disabled and spend time with him and not just be self-absorbed, self-centered, superficial, concerned about having fun and going along with the crowd.

How can we help our children become virtuous? An educational consultant, James Stenson, says there are three ways: 1) The example of parents and adults because children imitate what they see; 2) What are children led to do? What do we permit and what do we correct? 3) Do we talk about honesty, punctuality, self-control, hard work, apologizing quickly, following through on commitments, friendliness, politeness, prayerfulness, etc. Do we celebrate these things more than grades?

How can we help our children become virtuous? An educational consultant, James Stenson, says there are three ways: 1) The example of parents and adults because children imitate what they see; 2) What are children led to do? What do we permit and what do we correct? 3) Do we talk about honesty, punctuality, self-control, hard work, apologizing quickly, following through on commitments, friendliness, politeness, prayerfulness, etc. Do we celebrate these things more than grades?

The God who inspires us to imitate Him is also the God who gives us the grace to do it, so it’s very possible. Now we see the importance of prayer, right? To repeatedly choose the good requires a lot of spiritual strength. That’s why we need prayer and the sacraments so much (CCC 1811).

There are two people who always give me hope whenever I get discouraged, thinking I’ll never grow in virtue: St. Peter and St. Teresa of Avila. It took St. Peter his whole life to continuously grow in virtue. Two months ago, we talked about how he, even at the end of his life, was running away from the cross. But Jesus gave him strength so that eventually he could offer his life for Jesus. And St. Teresa of Avila spent the first 20 years of her life in the convent as a lazy and lukewarm nun, then had a conversion. So, it was God who helped these two very imperfect people eventually reach heroic virtue.

There are two people who always give me hope whenever I get discouraged, thinking I’ll never grow in virtue: St. Peter and St. Teresa of Avila. It took St. Peter his whole life to continuously grow in virtue. Two months ago, we talked about how he, even at the end of his life, was running away from the cross. But Jesus gave him strength so that eventually he could offer his life for Jesus. And St. Teresa of Avila spent the first 20 years of her life in the convent as a lazy and lukewarm nun, then had a conversion. So, it was God who helped these two very imperfect people eventually reach heroic virtue.

Never get discouraged by your sins. Getting up after we fall and going to confession again and again, after we sin—that is a virtue, the virtue of perseverance. St. Paul says, “Where sin increased, grace abounded all the more” (Rom 5:20).

Let’s put this all in perspective using the story of the rich young man. When the rich young man went to Jesus, he asked, “Good Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” Jesus answered, “You know the commandments: ‘Do not kill, Do not commit adultery, Do not steal, Do not bear false witness, Do not defraud, Honor your father and mother.’” In other words, live a virtuous life. The young man said he already did these. But there’s more to life and he knew it! Then the passage says, “Jesus looking upon him loved him [because he is good and precious in God’s eyes], and said to him, ‘You lack one thing; go, sell what you have, and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me’” (Mk 10:17-21). Yes, God wants virtue, but even more important is our relationship with Jesus, to follow and love Him.

We are born good, but we have to grow in virtue, and the greatest virtue is to love Jesus.