God is calling us to understand the big story of our faith, today. In other words, what’s the essence of Christianity? We’re going to answer this using a very practical scenario which builds upon years of talking about our relationship with God, the reality of free will, and consequences. Most people here are ready for this. If you’re a guest here today, welcome. I hope you and all of us find it thought-provoking and resonant with our hearts.

[Listen to Fr. Justin’s homily here.]

[Part 1]

[Part 2]

We’ve talked before about the reality of mortal sin, which has three conditions: a gravely wrong action that we know is wrong and still freely choose to do. If we choose this, by definition, we separate ourselves from God, and, if we die in this state, we don’t get sent to hell, we choose hell—God just ratifies our choice.

The only way our relationship with God can be repaired is by Confession, because, when we’re spiritually dead, we need someone else to resuscitate us spiritually, just as in baptism.

The best way to understand this is with the analogy of a marriage. I knew a husband who, in his forties, left his family for a younger woman because he said he had to find himself. His wife and three children were devastated, and that marriage is completely broken. That’s the reality of choices and action: He did something gravely wrong, knowing it was wrong, and still chose it. Can it be repaired? Only if he confesses, if she forgives him, and he does penance, and rebuilds trust and love.

Now here’s the practical scenario: Let’s say I commit a mortal sin. I’ve freely chosen hell. But, with God’s grace, I want to reconcile with Him. However, on my way to confession, one of you bad drivers hits me and I die. Question: Do I go to hell?

By analogy, let’s say that husband I mentioned wants to apologize to his wife, decides to go to Confession, but gets hit by a car on the way, and dies. Is he reconciled with his wife?

To answer this scenario, we need to know the essence of the story of Christianity, of which we get a snapshot in today’s Gospel. In the Gospel, there are three ways we learn the essence of Christianity, and they all have to do with Who Jesus is.

First, did you notice that three groups of people all tempt Jesus in the same way? They all tell Him to come down from the Cross and save Himself. “The leaders scoffed at Jesus saying, ‘He saved others; Let him save himself if he is the Christ of God, his chosen one! The soldiers also mocked Jesus… saying, ‘If you are the King of the Jews, save yourself!’… One of the criminals who were hanged there kept deriding him and saying, ‘Are you not the Christ? Save yourself and us!’” (Lk 23:35-37,39). By tempting Him, they’re getting to the root of Jesus’ identity: is He God or is He merely human? Humans always save themselves at the expense of others. But Jesus is God, and God is love, and love gives, and love sacrifices for others. He loves even when He’s surrounded by evil—that’s proof that He’s God. Only God would completely love people who don’t love Him.

He also proves the extent of His love for us by going to extremes. He could have died for us in a less gruesome way. But the Cross shows how much we’re worth. He did all that for you and me. Do you realize how infinitely precious you are?

And He shows how bad sin is. We take sin lightly; we’re so naïve. We don’t realize how devastating adultery is, how harmful pornography, sex outside of marriage are, getting drunk is. They seriously harm the human person.

The second way we know the essence of Christianity and Jesus’ identity is: “There was also an inscription over him, ‘This is the King of the Jews” (Lk 23:38). This is a humiliation, a king who’s naked and executed—who would follow such a king? But He accepts it without any thought of revenge. He even prays for His persecutors’ forgiveness, a prayer which changed the world, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Lk 23:34).

But Jesus is a king: He’s king of the universe; instead of a throne, He rules from a Cross; instead of being served, He serves; instead of robes, His nakedness shows His vulnerability, which is actually power, because not even nakedness can stop His mission. He’s a king Who rules with love, and shows that obedience to truth and goodness are His law.

There are two criminals crucified with Him. One derided Him, “but the other rebuked him, saying, ‘Do you not fear God, since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed have been condemned justly, for we are getting what we deserve for our deeds, but this man has done nothing wrong’” (Lk 23:40-41). There’s been so much written about the fear of God. Modern people don’t talk about it because it’s true that it can be misunderstood and harmful, but it’s also true that we’ve sanitized God of anything that might be remotely displeasing.

Remember I told you about a friend of mine who, during dinner, and according to his religion, wasn’t supposed to be eating the food that he ordered? I asked, “So why are you eating it?” “I think God understands that I really like this food.” His image of God is a pushover. That kind of god would never die for us because there’s nothing serious about him.

But God is a father Who’s serious about loving us, so serious that He sent His only Son to save us, and we should have a healthy fear of hurting our Father, and a fear of punishment. St. Hilary, in the 300s, noted three things about fear of the Lord according to the Bible: 1) It must be taught, because it’s not ordinary fear, like fear of animals or suffering; 2) It consists in love, and is shown by obedience to God; 3) There are always blessings attached to fear of the Lord.

This criminal, often referred to as the good thief, has this good fear of the Lord and recognizes the seriousness of his own sin and takes responsibility. He doesn’t make excuses: He says he’s condemned justly, is getting what he deserved for his actions.

Now we have the answer to our original question. If I commit a mortal sin, and die on the way to confession, my sins are not forgiven. I separated myself from God and die separated, and so I’m eternally separated—that’s the reality of freedom and sin, and we should take it seriously; we only have one life. This is the first part of the answer.

If we can accept this truth of reality, then the second part of reality will make sense as well. In fact, if we don’t get the first part, we won’t get the second.

Now here’s the third way we know the essence of Christianity and Jesus’ identity: “Then the good thief said, ‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.’ Jesus replied, ‘Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise’” (Lk 23:42-43). The good thief makes a prayer, an act of faith, trust, and hope. He recognizes Who Jesus is, that He’s God, that He’s so serious about sin that He’s dying for us and is ready to forgive up to the last moment! Jesus reveals that He’s the king of mercy, and guarantees heaven to the thief.

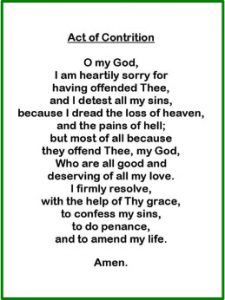

So, if we commit a mortal sin, go to Confession as soon as possible. But, in the meantime, make an act of perfect contrition with the firm resolution to go to Confession as soon as possible, as this will restore us to a state of grace, meaning, it will restore our relationship with God, and, if I get hit by one of you bad drivers on my way to confession, I won’t go to hell (CCC 1452; cf. CIC 916).

There are two conditions to this:

1) A perfect act of contrition. Imperfect contrition means we’re sorry because we’re afraid of hell whereas perfect means we’re sorry for our sins because we’ve hurt our Father. Both are good, but one’s better. Archbishop Sheen says it’s like a child who lies, and then says, “I’m sorry, Mom, I guess I can’t go to the picnic,” while another runs up to her parents and says, “I’m sorry for hurting you, Mom, Dad!” Here’s the prayer on the flat screens:

2) A firm intention to go to Confession as soon as possible. The Church doesn’t specify a time frame, but it seems to me that within a week is reasonable. Obviously, we need to make time for this.

If we do these two things, then we will be in a state of grace. This is something I’ve never taught here before because there’s a huge risk of abuse: Many Catholics hear this, and then never go to Confession, take Communion liberally, and never overcome their sins. And every time they take Communion in a state of mortal sin, they commit another mortal sin and harden their hearts. They don’t get the first part of the story, and so the second part is no use to them. Remember: If we’ve committed a mortal sin, we still don’t take Communion.

Now, I can’t read someone’s soul, but it seems to me that, if we make an act of perfect contrition and then don’t go to Confession as soon as possible, we’re playing games with God, we’re taking our eternal life in our own hands, and we’re sinning against God again.

Now, a fair question is: If we can receive forgiveness of mortal sins directly, why go to Confession? The answer is: If you get cancer, do you pray directly to God or go to the doctor? Both. In the same way, if we commit a mortal sin, do we make an act of perfect contrition or go to a spiritual doctor? Both. Jesus gave us Confession because we are physical beings and need physical signs of forgiveness. Confession actually helps us grow because psychologically it’s real; we actually hear our sins out loud and encounter Jesus’ mercy.

Also, the Church teaches that, even if we’re restored to sanctifying grace by an act of perfect contrition, we should still not receive Communion until going to Confession (CIC 916). The two acts of perfect contrition and Confession should be completed first before taking the Eucharist, and it seems to me that waiting is a good penance to atone for our sins.

This practical scenario which most of us have encountered or do encounter, points to the big story of Christianity.

For the past three months, we’ve been discussing Made for Mission. We share in Jesus’ mission, to help people know this story.

Use two examples to explain it: the story of marriage, because man’s relationship with God is described by the Bible as a marriage, and people understand that relationship. The Bible is about a love story, and it’s even God’s love letters to us. And our sometimes-broken marriage with Him can be restored!

In addition, use the story of Jesus and the good thief: This explains how sin is real, that Jesus is God, what He did for us, how precious we are, how there’s a time limit but still a chance for mercy. That’s the essence of Christianity.