I once shared a true story that left some of you confused. It was about Ann. She asked her counsellor, “Dr. Chapman, is it possible to love someone whom you hate?” referring to her husband, Glenn. Brothers and sisters, dear guests, let’s put ourselves in her shoes, or think about the people we know in a similar situation.

(Listen to Fr. Justin’s homily)

Ann’s love for Glenn had been killed by ten years of criticism and condemnation, and her emotional energy and self-esteem were almost destroyed. One day, Dr. Chapman read to Ann the words of Jesus that we heard today: “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you” (Lk 6:27). Then he suggested an experiment: If Ann, for six months, could love Glenn in a way he understood and appreciated, his emotional need for love would be met and then he’d start reciprocating.

Because her deepest desire was to save their marriage, she decided to do it. The plan was: She’d go home and say to Glenn, “I’ve been thinking about us and I’ve decided that I would like to be a better wife to you. So if you have any suggestions as to how I could be a better wife, I want you to know that I am open to them” (Dr. Gary Chapman, The 5 Love Languages, 158). Whatever his response was, she’d accept it. Then she’d start doing specific things and set goals to love him in ways he understood and appreciated. Could we do this with the people in our lives who hurt us? Believe it or not, Ann did this, and “saw a tremendous change in Glenn’s attitude and treatment of her. The first month, he treated the whole thing lightly. But after the second month, he gave her positive feedback about her efforts. In the last four months, he responded positively to almost all of her requests… Glenn never came for counselling, but… to this day… swears… that (Dr. Chapman is) a miracle worker” (Ibid., 162).

When I first shared this story, someone asked if Ann was taking all the blame and Glenn was getting off easily. Some women, for example, in abusive relationships, convince themselves that the abuse is their fault. Jesus commands us to forgive (Lk 6:37), but when does forgiving become enabling? In other words, when does forgiving mean giving people permission to hurt and continue causing harm? So, the question today is: How are we supposed to fulfill Jesus’ command?

Let’s look at the Scriptures: “Jesus said to his disciples: ‘I say to you that listen: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you” (Lk 6:27-28). The answer to our question comes from the definition of love, which, according to St. Thomas Aquinas, means to will the good of the other. This doesn’t mean having good feelings toward those who hurt us, but wanting what’s good for them, including that they stop sinning, that they change, maybe even that they are punished—why? Because that’s good for them.

Forgiveness does not mean excusing people’s sins, as if they were acceptable or unintentional. In 1991, there was a Saturday Night Live sketch called “Dysfunctional Family Feud,” where a family is on the game show and members of the family constantly insult each other. At one point, the father calls the son “Stupid,” and the older brother tries to defend him, but the younger brother says, “It’s alright, Steven, I am stupid.” There are some people who try to keep peace by not standing up to aggressors, but that’s not love, it’s a lack of courage. Forgiveness means, “What you did against me was wrong,” but I will try, if possible, to re-establish good relations with you (Germain Grisez, The Way of the Lord Jesus, vol. 2, Living a Christian Life, 311).

Three weeks ago, we talked about challenging ourselves as a community, and me as a priest not to hold back. So now I’m going to challenge you: One reason why we have trouble with loving our enemies is because we think love means being nice. Four times now we’ve talked about not being nice, because nice people tend not to have courage, and tend not to stand up against evil (Fear of Judgement Becomes Fear of Hurting Jesus; What a Disciple Is; Laying Down One’s Life; Why I Gave Up My Lightsaber). Of course, be kind! However, the word ‘nice’ in our culture has been sapped of the possibility of doing the right thing, which hurts people. Saying “No” to our kids’ wants isn’t nice, but it’s good! Just as punishment isn’t nice, but it’s virtuous! Standing outside B.C. Women’s Hospital and praying for an end to abortion doesn’t feel nice, but it’s the right, loving, and respectful thing to do. Niceness is a shallow idea deeply rooted in our culture, and it’s one reason why we struggle to forgive others, can’t stand up for ourselves, and can’t confront evil. I’ve even met people in positions of authority who are charged to do the right thing, to stand up against evil, but choose not to because they want to be considered nice. And I want to say to them, “You’re such a coward. We’re depending on you to help us, but you want to be nice.”

Jesus wasn’t nice the way our culture understands it; He was virtuous. On April 7, we’ll hear Jesus say to the woman who committed adultery, “From now on do not sin again” (Jn 8:11), because adultery is gravely wrong. Teach your children to be virtuous, don’t talk about being nice, and then people won’t take advantage of them.

Let’s apply this to Ann. Dr. Chapman and she never said that what Glenn was doing was right; she never blamed herself. The Church teaches that in situations of “grave mental or physical danger to the other spouse or to the offspring” (Canon 1153) couples can separate. This isn’t divorce, because Jesus teaches that divorce was never planned by God (Mt 5:31-32, 19:3-9; Mk 10:2-12; Lk 16:18). Separation means no longer living together, with the bond of marriage still intact. Ann could have left because of grave mental danger, and that would be a loving thing to do. But what she did was, through the grace of God, choose to do something also loving: Increase her love, and that converted her husband.

Let’s apply this to Ann. Dr. Chapman and she never said that what Glenn was doing was right; she never blamed herself. The Church teaches that in situations of “grave mental or physical danger to the other spouse or to the offspring” (Canon 1153) couples can separate. This isn’t divorce, because Jesus teaches that divorce was never planned by God (Mt 5:31-32, 19:3-9; Mk 10:2-12; Lk 16:18). Separation means no longer living together, with the bond of marriage still intact. Ann could have left because of grave mental danger, and that would be a loving thing to do. But what she did was, through the grace of God, choose to do something also loving: Increase her love, and that converted her husband.

Whatever moral choice we make, we’ll know our heart is pure and strong if we do the simpler part of what Jesus teaches: “Bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you” (Lk 6:27-28). Blessing in this case (the word for ‘blessing’ here in Greek is eulogeite) means to speak well of our enemies. We’re not going to lie and cover up their sins, but we’re also not going to take advantage of their sins and publicize them needlessly. As for prayer, there was a point in my life when I didn’t want to pray for some enemies, because I thought, in my immaturity, that by praying for them, they’d have an easy life, and I didn’t want them to have that gift. That’s wrong on two counts: 1) I didn’t want what’s good for my enemies, which isn’t love; 2) I didn’t want what God actually wanted for them, which isn’t an easy life and getting off easily, but a good life, meaning that they stop sinning.

When Jesus says, “If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also; and from anyone who takes away your coat do not withhold even your shirt” (Lk 6:29), all Scripture commentators say that this doesn’t mean being a doormat and enabling people, but avoiding retaliation (Ignatius Catholic Study Bible, 118. Pablo T. Gadenz, The Gospel of Luke, 133).

Forgiveness is a choice, not a feeling. It starts with the choice to not hurt people back, to pray for them, and then that eventually changes our feelings towards them. Only with time will the bitterness and resentment fade.

Forgiveness is a choice, not a feeling. It starts with the choice to not hurt people back, to pray for them, and then that eventually changes our feelings towards them. Only with time will the bitterness and resentment fade.

Yes, forgiveness can be genuine even if we don’t feel it. We can choose to will someone’s good, while at the same time still feeling the pain they caused us, still feeling that we want to get back at them—that’s just a temptation, not a lack of forgiveness.

Forgiving is different from forgetting. We can forgive but maybe never forget. That’s why Jesus tells us that we must forgive “seventy times seven” (Mt 18:22). The pain may always come back, and so we’ll have to forgive once again.

Jesus says today, “Love your enemies, do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return. Your reward will be great, and you will be children of the Most High; for he is kind to the ungrateful and the wicked. Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful” (Lk 6:35-36).

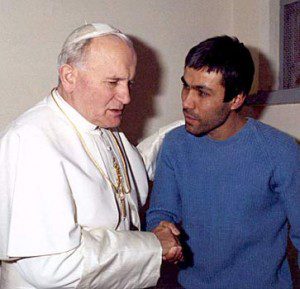

In this season on the Eucharist, we need to think about the Eucharist and our enemies. St. John Paul II said that “eucharistic worship constitutes the soul of all Christian life,” (Domincae Cenae, 5) and teaches us how to love our neighbour. “(The Eucharist) shows us… what value each person… has in God’s eyes, if Christ offers Himself equally to each one, under the species of bread and wine” (6). Wow! If Jesus offers Himself in the Eucharist to even our enemies, they must still be loved by God and have dignity. Now, if they’re in a state of mortal sin, because they’ve abused people, then they shouldn’t receive Jesus until they go to Confession, but the point is: Jesus still offers Himself to them, even if they’re not disposed to receive Him. St. John Paul continues, “If our Eucharistic worship is authentic, it must make us grow in awareness of the dignity of each person,” especially our enemies.

There are two things we need to have in order to love our enemies: 1) The right understanding of forgiveness, which Jesus has just given us; 2) The grace to love as Jesus.

In your pews are the prayers of forgiveness that we used two years ago. Please take (or print both Prayers for Enemies) and use them as starting points for prayer. And we should go to Confession, confessing our lack of forgiveness, because we need to be purified of our own sins, and once we encounter the Father’s mercy to ourselves, it’ll be easier to pass it on to others (Cf. CCC 1458).

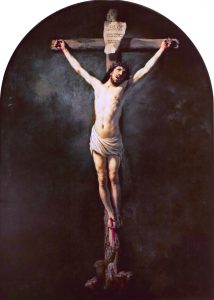

A spiritual director once gave me good advice when I felt angry with some people in my life years after they hurt me. She said to imagine myself with Jesus on the cross, and ask Him for the grace to love them as He does, and not to leave my prayer until I felt the same love as He does. This spiritual exercise gave so much grace: That’s when I was able to let go of my ill will towards them.

That’s how we love: Looking at people the way Jesus does, and getting strength from Him!

Two final stories: One of my seminary professors once told us about a woman whose husband committed adultery. She went for counselling, shared her story and pain, but the healing only started when the doctor lovingly asked her, “Are you going to stay angry forever?”

Second, a priest once told a group of seminarians that every time we refuse to forgive, we’re the ones who hurt ourselves. Whatever harm people did to us is in the past, but every time we refuse to forgive, we hurt ourselves again. So, I realized: He’s right! I keep on bringing these old hurts up, living in the past, and choosing not to let go—No! I want to be free. That motivated me to face the pain and, with God’s grace, choose to forgive people, and then I was free. As a result, the hurts slowly faded away!

God desires our good, and so we should desire the good even of our enemies.